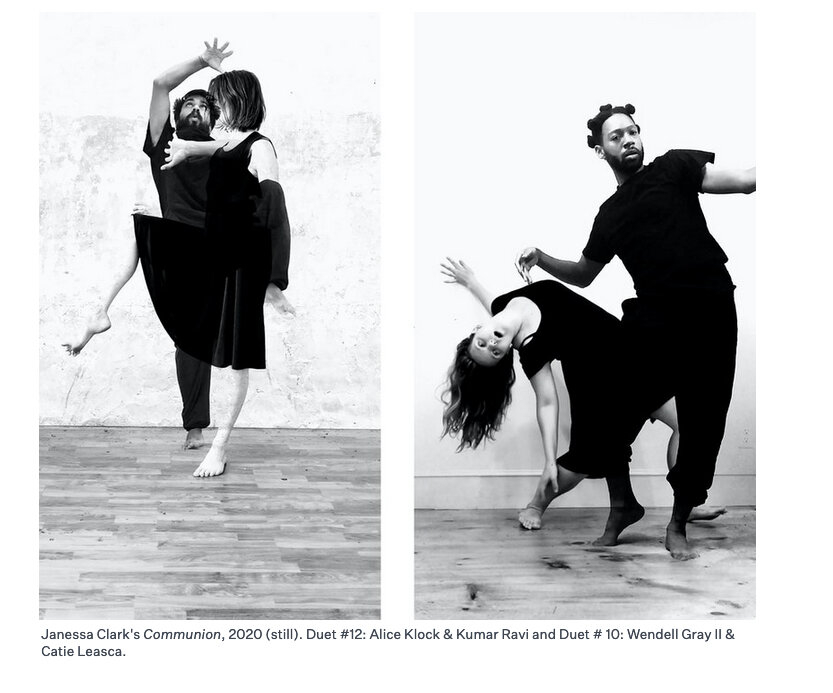

For those of us who have dedicated our lives to making live art, the COVID-induced shutdown, mandatory closures of performing arts spaces, and bans on social gatherings dealt a paralyzing sting. Finding the proverbial light at the end of the tunnel has been elusive to many, but the obstacles have also paved the way to happy accidents. I conversed in November—across continents and over email—with the Brooklyn-based, Swedish American choreographer Janessa Clark about her deeply collaborative and wholly virtual performance project, Communion. In this work, Clark brings together 40 dance artists and eight composers to create virtual duets across the divide of time and space—for instance, one duet featured Leslie Kraus in Norman, Oklahoma dancing with Ogbitse Omagbemi in Berlin, Germany; yet another saw Doug Elkins in the New York City paired with Sharon Estacio in Florence, Italy. With Communion, Clark managed to create a wide-reaching, hopeful, and empowering project as the pandemic rages on across the globe.

Ivan Talijancic (Rail): The pandemic has been particularly disruptive to those of us working in the live arts—how did you initially respond to the notion that rehearsing in-person with collaborators and performing to a live audience would not be possible for an undetermined period of time?

Janessa Clark: To be honest, I freaked out a little at first. I wondered what was going to happen to my career. Even though a healthy amount of my recent work can be viewed online, my live projects felt like they evaporated. Rehearsing and collaborating exclusively online was a foreign concept to me in that moment. I was due to start a new project and suddenly that—and everything else I had coming up—was canceled for the foreseeable future. My tour to Ukraine: postponed indefinitely. It was a gut punch. In some ways, I felt like my world had gotten significantly smaller in those early days, but on the other hand, I’m no stranger to time-compressed art making or dealing with unique conditions, and within those constraints, I tend to discover pathways that I would have never otherwise taken. I initially thought sheltering in place was going to be an insurmountable limitation, but that perceived “lack” actually forced me to be creative, to be curious.

Rail: You have been mixing media in your work for quite some time now. Do you feel like your multidisciplinary background gave you a wider array of tools to cope with the limitation of creating and presenting work in a strictly virtual setting?

Clark: Perhaps. As you mentioned, my work has been multidisciplinary for a number of years, so I was “prepared” in that I quite often engage with dance and visual media, but usually I am developing those experiments into pieces for live events or to weave into interactive installations. So, suddenly, I was faced with the notion that the virtual aspect was all that there would be. It was strange to not have any idea what I would even work on in lockdown, or with whom, or when the public would see my work again, or when I would see anyone’s work. I feel fortunate that some of my work adapts well for social media platforms and online festivals, but it was the question of “making work” that was challenging. Another significant component of my practice is that much of it is socially engaged in some way. The viewer is usually a collaborator or an activator. So it was initially tricky … trying to wrap up all these threads into something that felt fulfilling.

Rail: What was the initial impetus for your Communion project? How did the idea come about, and has it evolved as the pandemic continues?

Clark: Right before the lockdown, I had been talking with my dear friend and fellow choreographer Laura Peterson about starting research in the studio for a new piece. When we all began sheltering in place, I asked Laura to film herself improvising in her living room and to send it to me. At first, I was planning to screen it on my studio wall, life size, while improvising in response. Instead, I had the idea to also film myself and arrange our footage side by side in my editing software so that I could make some compositional decisions. Out of curiosity, I layered us and it was like a “eureka!” moment. I asked Laura for more footage, this time against as plain a background as possible so that blending with my white-box studio space would be more seamless. The results were magical to me and thus the early concept for Communion was born. The name came a bit later. I was instantly in love with the duet: how it felt to dance together with someone dear to me, while also remaining separated by distance and the pandemic. It was poetic, but also so visceral … and on top of that, I deeply enjoyed the process. I continued to refine that first duet multiple times until I located the aesthetic I was after. The response was so heartfelt upon sharing it with Laura and a few others that I realized I had stumbled upon my next project.

Once I had this seed for Communion, I wanted to craft it in such a way that it would feel as close to “togetherness” as we were going to get during lockdown. I curated 20 artists I wanted to invite into the project. I then asked them to, in turn, invite a duet partner of their choosing; I envisioned everyone dancing with someone they longed to share common space with. Sometimes this manifested as career-long partnerships, other times it was dancers who had worked together in the past but hadn’t seen each other in years, and still others chose a partner they had never even met, someone whose dancing they’d admired from afar exclusively on social media. I invited composers with whom I had previously collaborated, as well as some whose works I’d listened to on repeat and hoped for a chance to work together; others yet were brought in by the dancers in the duets. It felt like all of us were converging for an event that would feed our need to be creative. It was in that spirit that I quickly landed on the name Communion. The space we hold is a virtual one, but it is also a spiritual one: each of us enacting our gifts in order to touch the divine. I couldn’t have titled it anything else—it was always right there. For me, it has evolved far beyond the simple, beautiful idea of creating virtual duets. It has somehow become an archive of our collective experience within this pandemic, within the chaos of institutionalized racism, and the political climate. Within this crescendo it feels like hope. For me, at least. This is why I am compelled to make it.

Rail: What has the response been so far—from the viewers and the collaborators alike? And what is your own take, now that the project has been up and running?

Clark: I mean, wow, what can I say? People absolutely love these duets. I am so grateful that the reception has been strong because I made this series hoping to light our isolated worlds with the faces that we would otherwise flock to the theater to see live. From the perspective of viewers, I think that it’s partly some fascination as to how the dancers are able to be blended into the same virtual space, partly joy at seeing the 40 dancers who came together in the pieces, and partly the wonderful sound scores that have been offered by the eight incredible composers.

People message me and email me frequently expressing their thanks. I hear about how emotional viewers become when they watch each piece. I can relate; there are some that I tear up watching still to this day. People have so many questions, they are curious, and that is exciting and nourishing for me. When I think about this project, I am always filled with a deep sense of love and appreciation. These artists are some of the finest in the world, and they have opened their hearts to collaborate on this with me. I have never experienced such wide-reaching generosity, and from all corners of the world. This entire project has been created on a voluntary basis—no one has received any money (and I am very upfront about this aspect as I have historically always had a budget for artists). It has been a collective meditation for all of us, I think, to work on something that is bringing people solace in a time of such tension.

Rail: Do you feel the way in which you've had to reframe your artistic approach due to the pandemic will have a lasting effect on your practice? What are the takeaways?

Clark: Totally. My practice has been one of co-authorship and social-engagement for many years. This past year I’ve had to dig deep to ensure that those aims stay alive. The format has, of course, moved away from the live works and installations I normally develop, but as I’ve gravitated more and more into a multidisciplinary practice, it’s almost like 2020 became my laboratory for expanding my skills and capacity. I am forever changed by this year of trying to make work in isolation and intense unrest. We need art in this new frontier. I, for one, am very much looking forward to further combining disciplines and experiences for the viewer, whether live, virtual, or somewhere in between.

Rail: Any wisdom to share with your artistic peers who may feel stuck while the restrictions on gatherings and performances are still in place until further notice?

Clark: I think there is a real beauty in the mess; in the experiments that perhaps have no definitive outcomes. I think that experimentation in new forms, on new platforms, and with new people can be thrilling. So many talented artists are filling my media feeds and it’s giving me life, especially the artistic activism. I am humbled by their offerings. There’s room for all of it. Artists have that task of being the visual, embodied, and aural documentation of our impossibly complex times. We will do what we have always done, we will figure it out and find a way.

You can think of restrictions as limits, sure, but instead how about as a chance to strengthen your skills and your tenacity? Make the work you need to in order to survive, in order to stay curious and engaged. Make a ton, throw it out, start over again. This is what we do. Communion is my form of activism, in a way. I had to dive down deep and pull this out of me so that I could breathe again.

Link to full article: https://brooklynrail.org/2020/12/dance/JANESSA-CLARK-with-Ivan-Talijancic